As the 23-24 season comes to an end, as far as the actual harvests are concerned, we can safely say that it has been a year of tremendous learning. Without wanting to repeat what everyone knows about how difficult it has been and how complicated it has been for us to reach a successful conclusion.

Never since cherries have been exported have we had so many adverse weather conditions for production. I have always argued that success or failure in this area depends to a large extent on the weather. Never has this been more true than this year.

We started with a very hot and dry summer, and a high incidence of phytophagous mites. Then an autumn that was too mild, which made it difficult to enter dormancy. In this respect, fortunately, our productive area is very large, and although relatively young, the Ovalle area had given us insight into how to deal with these conditions. Therefore, I believe that having used a strategy similar to the one used there, in terms of managing water stress and early conditioning of the plants, allowed many of us to have a successful and timely leaf fall, with a good accumulation of reserves and an effective closure of buds.

But the mild autumn brought other, even worse consequences. The accumulation of cold has been the worst in recent years. Let us remember that the cold hours are the “fuel” necessary for the metabolization of reserves.

In addition, in June and then at the end of August, there were two very intense rains, the last one in particular with more than 300 mm falling in just a few days. This exposed a major flaw that strongly affected the development of our season: “The vast majority of our soils are not prepared to receive such a volume of water in such a short period of time.”

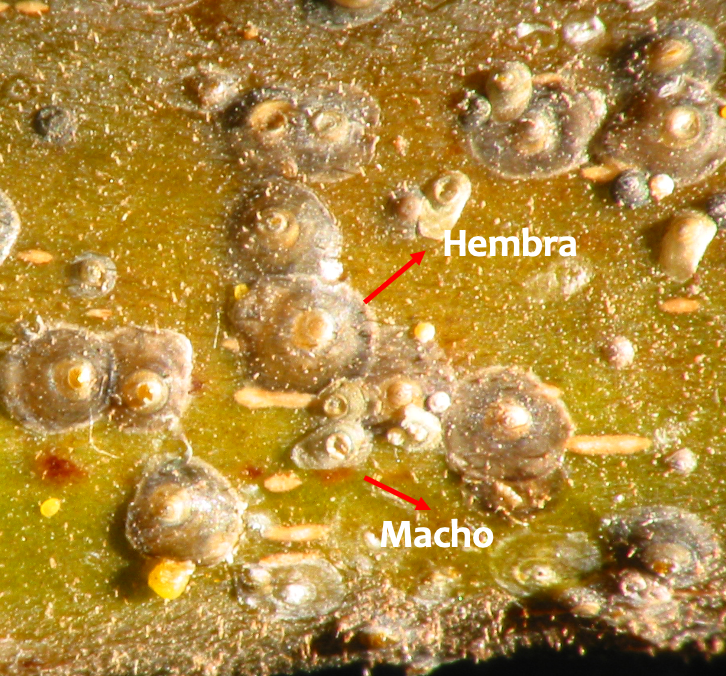

On the other hand, the beginning of September was quite cold and with a very poor accumulation of degree days. This meant that the phenological stages progressed slowly and on many occasions we saw that a long time passed between swollen bud and exposed bouquet and then from exposed bouquet to the beginning of flowering several more days, so we were forced to increase phytosanitary controls to avoid the development of fungal and bacterial diseases.

The previous season left us with some experiences, since there was considerably less rainfall during August 2022, which caused the soil to remain cold at the beginning of spring, so we had a late reaction of the plant in its root growth.

In the same year, we suffered large losses due to “pasmas” in varieties such as Lapins and Regina, and we learned that the plant exhausted its reserves before being able to absorb nutrients to cover the entire load.

So, for this 2023-24 season, given what happened during August and the cold weather at the beginning of spring, we took extra precautions, improving and increasing foliar fertilization during flowering and, added to all the inconveniences of winter, we were forced to use all the existing technological tools to ensure greater fruit set. This led to an increase in the cost of the programs and with quite dissimilar results, but which allowed us to draw conclusions.

In the earliest area, from the start of flowering, a phenomenon rarely seen began to appear. In the same orchard we had trees that flowered normally and soon we found some where there was practically no flowering and then there were no buds either. We also found damage to flower buds, and in extreme cases, damage to vegetative buds. It began to be known colloquially as “candied peanut type buds”. At first it was believed that it was the result of frost damage, cyanamide, etc. since it was very similar to what causes cyanamide poisoning. However, it was easily distinguishable from that one, since it occurred in the tree, both in the lower part, as well as in the middle or in the upper third, but it was also very common to notice that the tree next to it did not have it and then the next one did. It was a very irregular damage, except in those areas that suffered prolonged flooding or in lower orchard sectors, with heavier soils.

We quickly identified the intensity of the damage and, with greater reason, we also intensified the use of hormonal products to retain fruit set and all the tools we had at hand to improve fruit retention. And, in addition, by strengthening the applications of foliar fertilizers, we set out to reduce the effects of the evident future blight. We began to notice that the early zone was experiencing a significant loss in production and that in the middle and late zones these losses were much less noticeable. The damage manifested in fruit or vegetative buds was also less in those areas considered later or where the accumulation of winter cold was better handled.

With this, we appreciated early on that the areas with poor cold accumulation showed greater or lesser fruit set depending on the management of dormancy breakers and, above all, the type of soil.

In the later zone, however, the damage was considerably less. However, we were also able to observe that if this zone was associated with heavy soil, we had a considerable drop in production. If, on the other hand, the soil is light or the plantation is in rows, the production is considerably higher.

The rains in November forced us to work three times harder. The use of hydrophobic products and strategies for rapid drying were sterile for most of the early varieties. The rain, which exceeded 40 mm, caused the plants to absorb water, which reached the fruit quickly and without restrictions, causing damage from apical and equatorial cracks. Once again, the most affected area was the early one. The subsequent rains were less damaging, except for the Bing and Rainier varieties in the central area, which suffered the same fate as the early varieties, but this time with the last rain in November.

We arrived at the harvest and a new challenge was proposed to us, mainly to those in the most damaged areas: to excite the harvesters. So we had to go back to the harvests carried out using the “daily” or “semi-treatment” and “flowering” method, as we had not done for years. But the task was accomplished, and as the season progressed, the harvest conditions improved, of course not without difficulties, especially in terms of color uniformity. Another lesson: We use different methods and/or products to homogenize, some more, others less.

As a great and final lesson, and as a summary: The lack of cold can be compensated, in part, with the use of the technological tools that we have at hand. The use of nets, growth regulators and homogenizers can allow us to avoid this lack in a good way. In fact, we have already seen it a couple of seasons ago in the northern area.

However, I think that the great lesson that this season has taught me, at least for me, is that with very poor preparation and very high soil compaction, it is difficult to deal with problems like those seen this year. The main task is to improve root conditions, drain and clear low areas and, above all, bring life back to our soils.

I think I learned more in this one than in the last 10 years.